Art is About Finding Questions, Not Answers

Winfred Hawkins on self-expression, dyslexia, and the art world’s relatability problem.

Visit Winfred’s links: Web Youtube SoundCloud

Songs used in this episode are from Winfred’s unreleased project Da West Side, except “WhA-ChU Rekkon,” released on Youtube . In order, the track titles are “Give Me Strength,” “Rattlesnake Poison,” “WhA-ChU Rekkon,” and “Woke Up In A Strange Land.” A partial transcript of the episode is provided below. Listen to the audio for the full conversation.

It’s a clear Saturday morning, warmed in the promise of false spring sun. The front porch is filled with planters, and a knock on the door produces the smiling faces of family and the sharp cries of twin babies.

The house is cozy and Winfred directs us up the narrow stairs to his attic workspace. Stacks of books prop up sheets of painted plywood, wires running like roots along the spattered floor. The hum of amps and a desktop computer blends with the heat rising from the ground level, a terrarium of sorts. Winfred shows us a modified bass guitar, and sets some of his original music on loop in the background.

J: Shall we get into the interview then? We wanted to get a sense of your philosophy on art; where you’re at in your journey as a creator, and where you want to go. My first question is the biggest one. Why is art important?

W: For me personally, it pretty much saved me from a lot of situations. It’s been my escape for multiple different events in my life. And some of that comes from having dyslexia, and trying to express ideas to people who aren’t used to thinking in the abstract or conceptually.

Culturally, as a broader question, art shapes the consciousness of a people. Throughout history, the things that we know about cultures is because of the art they produced, be it pottery, sculpture, architecture, some music…We exist in the world through art.

I wrote a description to one of my pieces called White Out, and in it I said “Art has become lost in the ether of academia.” So you have people who kind of know too much talking about art in a sense. I say that because the more knowledge we have about a thing or the more fluent we are about it, the human condition comes in where we try to show off all the references we know.

J: So I want to dial into Montgomery specifically as your historical context. Can you talk about how Montgomery has shaped you as a place, and how that might be reflected in your work at all? Or how you think about this city and being from it?

W: One thing that has shaped me is my growing up Seventh Day Adventist. I don’t particularly prescribe to any religion now, but one thing I do like is the idea of knowing things for yourself. Don’t just take the pastor’s word for it, don’t take anyone’s word for it. Do your own research, and your relationship with spirituality is your business and no one else’s.

Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee around a Pomegranate a Second before Waking 1944, Salvador Dalí (left), compared to a drawing of the state bird of Alabama, Yellow Hamer, Lutea Avis by Eleazar Albin (right)

I was a traditional artist growing up. My dad was one of the first Black microbiologists in Alabama. He liked nature a lot, so he would have some books with birds and plants and animals and stuff, and I would practice drawing out of those books a lot. In high school when I first learned about Salvador Dali, I was like, hey, this is realistic, but a tiger don’t look like that. And I was like, wait a minute, I can interject other ideas that are not on this planet, and make it look realistic, and say what I want to say at the same time.

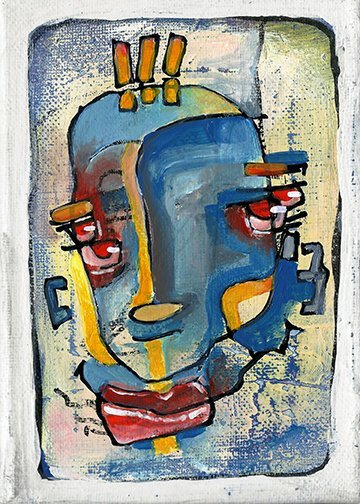

There was a piece that I was working on called Right Side Down, that expresses a personal struggle with institutions or authority or folks who are supposed to know better than you, and the other side of that, and which side is the right side, provided it’s not some hate speech. But that was the piece that had me thinking about how to communicate the stories and ideas in my head.

Right Side Down, Winfred Hawkins

J: What I’ve heard from what you just said was like authority, or religion, and those seem to be all over the place. Maybe there’s something else that’s unique to this place?

W: I would say the one thing would be time and space are unique here. Things don’t move fast here. You can walk and have private moments in public, and contemplate and think about things. I feel like one of the issues of the human condition is that we don’t practice mindfulness, and we don’t make the opportunity to sit down with our own thoughts. There’s always some tv on or screen on, and once you’re forced to be with yourself and only yourself, you get to understand your thoughts, and who you are as a person. I feel like living here has allowed me to do that moreso than living somewhere else.

J: I would like to swing back around to your process/practice, and maybe your history as a creative person. Could you talk about a couple of projects that you felt were successful, and maybe a couple where they didn’t turn out the right way, and some of the lessons you learned over time?

W: Well as an artist, you make a lot of things, so there’s a lot of failures. Even in this room, there’s a million failures. There’s a series of pieces that I felt were successful at the time. I did roundels for the Rosa Parks museum.

The Lone Passenger roundel, Winfred Hawkins, photo by Chris Flood

On a grand scale, I don’t think I have a major piece that didn’t come out right, and hopefully I never do. And the reason for that is that a lot of the stuff that I do is in private. I don’t like to learn in front of people, not because I’m embarrassed or anything. It’s because you’re not gonna understand what I’m doing or why I’m doing it.

J: Failure is such an important learning experience. This idea of failure as a way to experiment or try and make space. Your space is a place you’re failing all the time in private, and I think that’s fascinating. Cause when it does come out, not only will it be dope, but you can coherently explain it to you in a way that makes sense to you. That’s cool.

W: I only really started reading about dyslexia in the last few years. A lot of people have misconceptions that it’s a reading or writing problem, but those are symptoms. It’s really about how we process information.

That’s why I have to leave, cause people do not understand what I’m doing, or they will think that I’m doing something when I’m actually doing something else, and sometimes it’s time sensitive, so I don’t have time to debate or argue about what I’m doing and why I’m doing it. I just need you to be quiet and let me do it.

J: So, my last few questions are about the future. What is exciting you right now?

W: So, I’ve been trying to find artists that happen to be Black. I’m an artist full stop. If I choose to talk about Black issues, then cool, and if not, also should be cool. I’m not obligated to educate you on why things are the way they are. At the same time, I do think when you are put in those positions, it’s important to have some sense of awareness that I’m here, I have an opportunity that not a lot of people like me have.

A lot of things in the professional art space are just unrelatable, not because you can’t see what’s going on, but because they don’t speak to the human condition. For me and where I come from, I’ve got bigger worries than your little mark on a blank canvass. What are you trying to say to me? That’s where I’m more excited, finding Black artists that exist in the space that I want to be in, and finding out how did you do that?

J: What are you experimenting with now? What’s on your creative horizon? Or is that how it works at all?

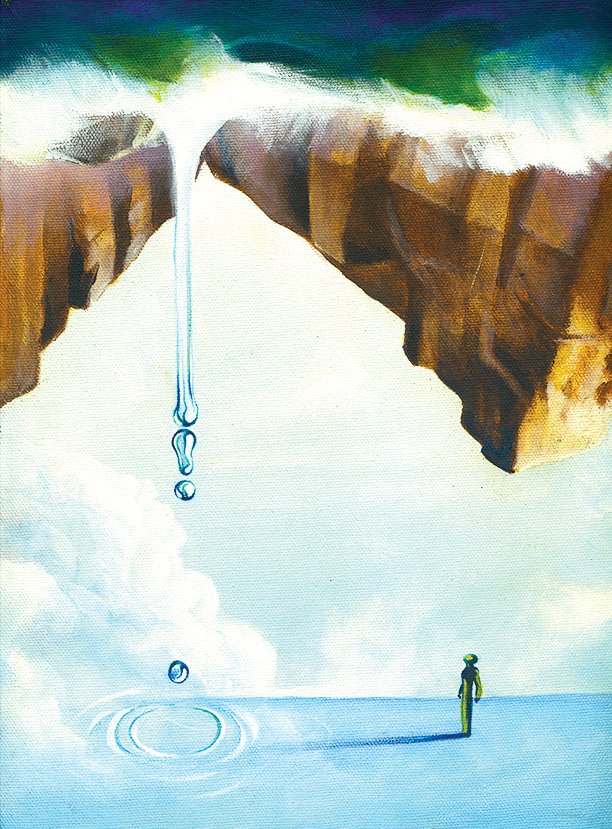

W: There’s something I’ve thought about with sound and visual artworks together, but I’ve never really produced any pieces specifically designed around that. Also I’m working on these pieces around the dyslexia thing. There is an ongoing series that I have with my left hand, it’s called The Walls Have Feelings, which is based on those urban spaces and how structures have memories. Buildings have feelings, whether it’s jails, random walls, people’s houses. They house memories; every mark on a wall or ceiling is a mark left by a person. Someone bumped their head and oops, there’s a mark.

Thinking about art education and nuance, a lot of my pieces have call outs to art history. Like one of the ideas behind these is Rothko, so you have this band of color, and another. But I take a Rothko and destroy it and put graffiti in it, because Rothko was very against the establishment of the posh and rich with million dollar pieces. So, I take some cues from artists like Michaelangelo, Raphael, or Rothko, or Malevich, or whoever. It’s just that I don’t really feel like it’s important to mention them unless it’s crucial to the conversation. It’s more important that we speak in a language that is current and understandable today. Use shapes and colors and marks that speak to today’s people.

Reality Is Not Real 39-3, Winfred Hawkins

J: How do we cultivate that understanding in people? What do people need to develop as artists?

W: They need curiosity, and they need diligence. Curiosity is when you see something you haven’t seen before, you notice it and say hey what’s that over there. Diligence is the drive to walk over there and find out what that is. I feel like a lot of times, because we’ve grown up in our society the way it is, we train the curiosity out of ourselves.

Observation is what I’m talking about, so how to enrich your life in ways that don’t cost money, which will elevate consciousness of a people, which will elevate their culture, which elevates things they will and will not stand for. Learning to find that poetry in everyday objects and everyday situations, not taking things for granted. Even comedy, the best comedy is when you take the most common thing, flip the perspective, and it becomes hilarious, because everyone has experienced that thing, but haven’t thought about it in that way. So they immediately have something to grab onto.